Difference between revisions of "Darwinbots3/Physics"

(Adding more info about solving a collision) |

m |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

We can define a relationship between the velocities before and after the collision using the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coefficient_of_restitution coefficient of restitution]. Which is basically a fractional scalar value between 0 (for inelastic collisions) and 1 (for perfectly elastic collisions). | We can define a relationship between the velocities before and after the collision using the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coefficient_of_restitution coefficient of restitution]. Which is basically a fractional scalar value between 0 (for inelastic collisions) and 1 (for perfectly elastic collisions). | ||

| − | : <math>v_{XPf} - v_{YPf} = -(1 + \epsilon) * (v_{XPi} - v_{YPi}) | + | : <math>v_{XPf} - v_{YPf} = -(1 + \epsilon) * (v_{XPi} - v_{YPi})</math> |

where: | where: | ||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

{ | { | ||

Vector rPerp = (point - body.Position).Perp(); | Vector rPerp = (point - body.Position).Perp(); | ||

| − | Scalar a = n.DotSquared(n) * body.InverseMass; | + | Scalar a = n.DotSquared(n) * body.InverseMass; // The resistance to linear acceleration |

| − | Scalar q = rPerp.DotProduct(n) * body.InverseMomentOfInertia; | + | Scalar q = rPerp.DotProduct(n) * body.InverseMomentOfInertia; // The resistance to angular acceleration |

q *= q; | q *= q; | ||

Revision as of 02:56, 28 April 2009

Basic concepts

Forces' linear affects

Any force acting on a body, at any point on a body, applies the same change in acceleration to the body's center of mass. Consider the diagram below:

__________ | | | | | X | <---| | |________| <---

Diagram 1

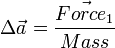

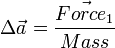

Where X is the center of mass for the body.  is exactly centered, so it produces no torque. The change in acceleration of the body's center of mass is given by

is exactly centered, so it produces no torque. The change in acceleration of the body's center of mass is given by  .

.

Let  have the same magnitude and direction as

have the same magnitude and direction as  . However it's applying its force at a different point on the body, and will produce torque. Even though it's off center, the change in acceleration for the body's center of mass is still

. However it's applying its force at a different point on the body, and will produce torque. Even though it's off center, the change in acceleration for the body's center of mass is still  .

.

Forces' angular affects

Consider Diagram 1 again.  will not produce any change in angular acceleration for the body, because it is centered.

will not produce any change in angular acceleration for the body, because it is centered.  will produce change in angular acceleration, because it is off center. In general, the torque (

will produce change in angular acceleration, because it is off center. In general, the torque ( ) produced by a force is given by:

) produced by a force is given by:

And the change in angular acceleration is given by:

Where:

-

is the scalar torque term.

is the scalar torque term. -

is the vector Force term.

is the vector Force term. -

is the vector perpendicular to the vector from the body's origin to the place

is the vector perpendicular to the vector from the body's origin to the place  is acting on the body.

is acting on the body. -

is the scalar angular acceleration

is the scalar angular acceleration -

is the body's scalar moment of inertertia.

is the body's scalar moment of inertertia.

Simple collision

__________ __ | | / | | | ___/ | | X |P___ Y | | | \ | |________| \__| Diagram 2

Consider a collision between two bodies: body X and body Y. They collide at point P. We assume that the collision takes 0 time. That is, the bodies "instantly" resolve their collision.

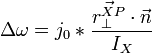

The change in angular and linear velocity for body X is given by:

where:

-

is the change in linear velocity.

is the change in linear velocity. -

is the change in angular velocity.

is the change in angular velocity. -

is the scalar impulse term applied to the body at point P to correct its velocity from the collision.

is the scalar impulse term applied to the body at point P to correct its velocity from the collision. -

is the scalar mass for the body.

is the scalar mass for the body. -

is the scalar moment of inertia for the body.

is the scalar moment of inertia for the body. -

is a vector representing the "normal" to the colision. In the case of the vertex-on-edge collision in Diagram 2, n would probably be

is a vector representing the "normal" to the colision. In the case of the vertex-on-edge collision in Diagram 2, n would probably be

-

is the vector perpendicular to the vector from the center of mass of body X to the collision point P.

is the vector perpendicular to the vector from the center of mass of body X to the collision point P.

Body Y likewise, but the changes are opposite in sign (equal and opposite reaction).

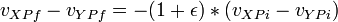

We can define a relationship between the velocities before and after the collision using the coefficient of restitution. Which is basically a fractional scalar value between 0 (for inelastic collisions) and 1 (for perfectly elastic collisions).

where:

-

are the final velocities of bodies X and Y at point P.

are the final velocities of bodies X and Y at point P. -

is the coefficient of restitution for the equation

is the coefficient of restitution for the equation -

are the initial velocities of bodies X and Y at point P.

are the initial velocities of bodies X and Y at point P.

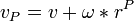

To find the velocity of a body at a given point, use the formula:

where:

-

is the velocity at a certain point on the body.

is the velocity at a certain point on the body. -

is the body's angular velocity.

is the body's angular velocity. -

is the vector from the body's center of mass to point P.

is the vector from the body's center of mass to point P.

Using all of the equations above, we can find  by the following algorithm:

by the following algorithm:

suppose we are supplied with:

a contact point P

a collision normal n

two bodies in collision, bodyX and bodyY

a coefficient of restitution e

Vector VelocityAtPoint(Body body, Vector point)

{

return body.Velocity + body.AngularVelocity * (point - body.Position);

}

Scalar ResistanceFromBody(Body body, Vector point, Vector n)

{

Vector rPerp = (point - body.Position).Perp();

Scalar a = n.DotSquared(n) * body.InverseMass; // The resistance to linear acceleration

Scalar q = rPerp.DotProduct(n) * body.InverseMomentOfInertia; // The resistance to angular acceleration

q *= q;

return a + q;

}

Scalar vXP = VelocityAtPoint(bodyX, P).DotProduct(n);

Scalar vYP = VelocityAtPoint(bodyY, P).DotProduct(n);

Scalar b = -(1 + e) * (vXP - vYP);

Vector rXPNorm = (point - bodyX.Position).Perp();

Vector rYPNorm = (point - bodyY.Position).Perp();

Scalar resistanceX = ResistanceFromBody(bodyX, P, n);

Scalar resistanceY = ResistanceFromBody(bodyY, P, n);

Scalar j0 = b / (resistanceX - resistanceY);

return j0;